Table of Contents

Kinship is culture, not nature

Kinship is culture, not nature

Week 5: Family matters

Ryan Schram

ANTH 1002: Anthropology in the world

Monday, August 29, 2022

Slides available at https://anthro.rschram.org/1002/2022/5.1

Main reading: Eriksen (2015)

Other reading: Carsten (1995)

Are genetic relatives your “roots”?

You can buy at-home DNA testing kits to discover your relatives and supposedly your ancestral origins.

Would you be interested in a “heritage” vacation in the land of your ancestors?

Valle, Gaby Del. 2019. “Airbnb Is Partnering with 23andMe to Send People on ‘Heritage’ Vacations.” Vox. May 22, 2019. https://www.vox.com/2019/5/22/18635829/airbnb-23andme-heritage-vacations-partnership.

Nature and culture

DNA-based ancestry reports want users to believe that they have a fixed, natural essence. In their philosophy,

- Kinship is an essence that one shares with one’s genealogical relatives. Kinship and family are relationships based on sameness.

- This essence is passed down unchanged over time. Kinship is continuous with one’s ethnicity and origins.

Do we in fact have natural relationships? What is the line between natural existence and social membership in a community?

- Everyone who has ever lived was already part of a larger social order, and had ties to other people when they were born.

- Children are dependent on adults and need to have an intensive relationship with adults over many years.

- There are no societies in which some form of kinship is not recognized.

- In each society and in every community, people organize kinship relationships differently, and each society assigns different degrees of importance to these ties.

Kinship is universal, but takes variable forms. A classic problem for anthropology. Which matters more?

Biological kinship and social kinship

Reproduction and birth are universal, but whether they count as kinship is different everywhere.

A useful distinction

- Genitor (is to) Pater (as) Biological (is to) Social

- Genetrix (is to) Mater (as) Biological (is to) Social

Everyone has a genitor and a genetrix, but pater and mater are positions in a social system.

In societies with temporary marriages,

- a child is created by a genetrix and genitor,

- and has a mater and maternal relatives,

- but does not have a pater and paternal relatives.

Some historical and contemporary examples are:

- Nayar (Nair) people of Kerala state, India (Gough 1961)

- Musuo (Na), Yunnan and Sichuan provinces, China (Hua 2001)

Many forms of family

I expect that the idea that family comes in many forms, and that people in different cultures have different ideas of families, is not surprising and controversial.

Yet do we see this diversity in family form the right way?

We need to see it from the inside, not from the outside.

- Terms like “extended” or “multigenerational” imply that the normal family is compact (?) and has less generations. Who says that’s normal?

- Nayar and Musuo families only “lack fathers” in eyes of others.

- Imagine what your own family looks like from another culture’s perspective: What’s it like to live in a multiple-parent household, hmm?

Kinship is a system of categories

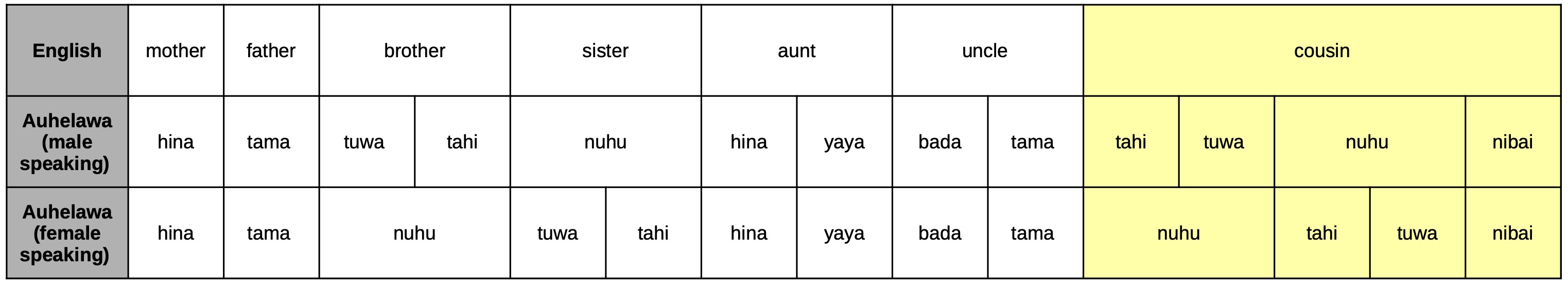

Compare these two different languages and their words for relatives (PDF version):

Learning terms for relatives in Auhelawa is not just a matter of translating.

What is a cousin?

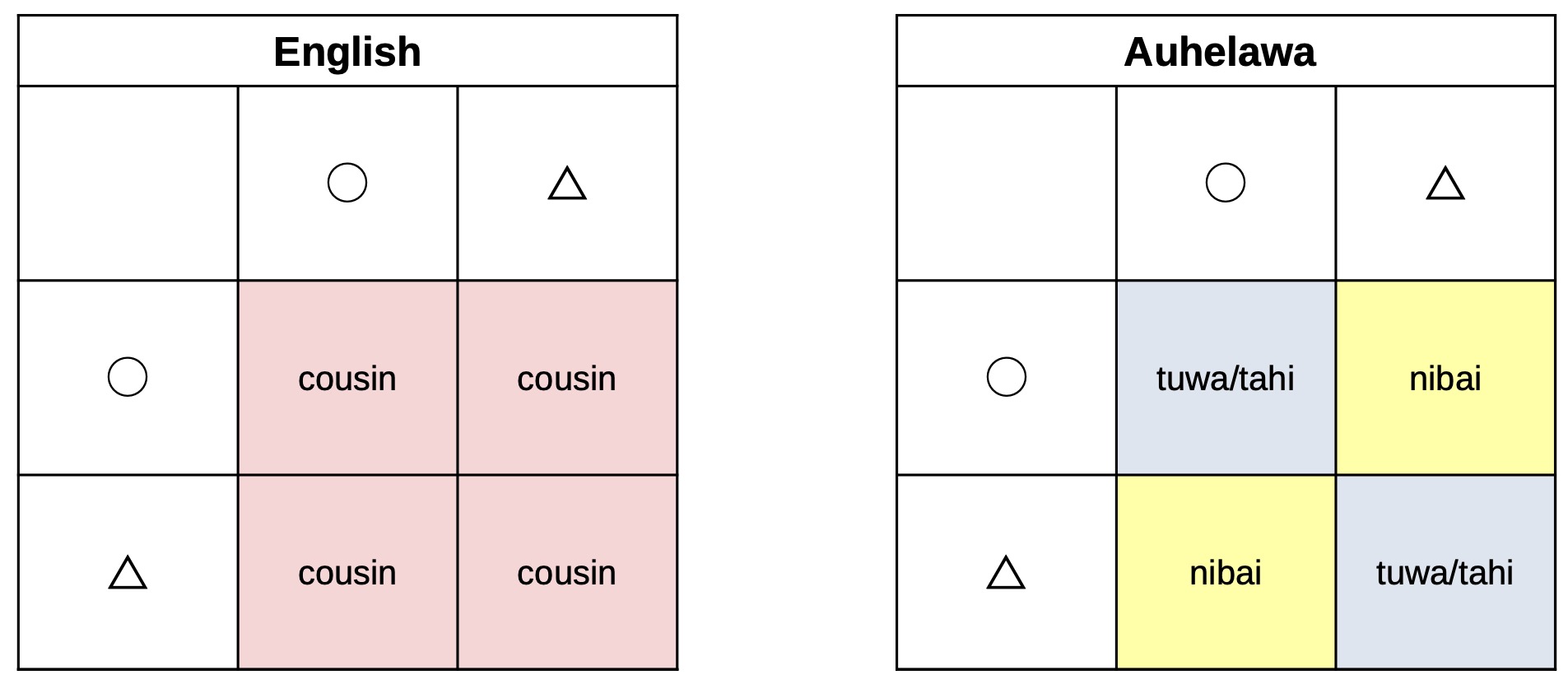

In English, several different people in different genealogical positions are called cousin. In Auhelawa, terms exist to make a very specific distinction among these people (PDF version):

[Column headings are parents and row headings are parents’ siblings.]

The distinctions made in Auhelawa are not unique. Many other languages make the same distinctions.

- Children of cross-sex siblings (M–F, F–M) are cross-cousins. Cross-cousins are called nibai in Auhelawa

- Children of same-sex siblings (F–F, M–M) are parallel cousins. In Auhelawa, parallel cousins are in the same category as children of one's parents, or siblings (tahi, tuwa, nuhu, or gelu as a cover term).

Categories of kin, groups of people, structures of societies

For many societies, tracing one’s kinship through either a mother or a father locates one in space, and in a comprehensive system of exclusive groups. One’s descent is one’s primary social identity (Fortes 1953).

- People of Nuer communities in South Sudan trace kinship relationships through mothers and fathers, but assign each child—and every person—to a group in which all members are related through their fathers, and descend through men from a single ancestor (Evans-Pritchard 1940, 6–7, 135–37, 142–47; see also Evans-Pritchard [1940] 2002).

- Auhelawa people do likewise, but through women. I am a member of Lucy’s lineage which connects me to her sisters, their children and to other people related to Lucy’s maternal line of descent through their mothers.

In societies whose kinship is used to construct groups based on unilineal descent, either matrilineal or patrilineal, everyone in the society belongs to exactly one group. Everyone has a place in a distinct group.

Kinship’s weak link: The proliferation of technical terms

Naming something does not mean we understand it.

References and further reading

Carsten, Janet. 1995. “The Substance of Kinship and the Heat of the Hearth: Feeding, Personhood, and Relatedness Among Malays in Pulau Langkawi.” American Ethnologist 22 (2): 223–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/646700.

Eriksen, Thomas Hylland. 2015. “Kinship as Descent.” In Small Places, Large Issues: An Introduction to Social and Cultural Anthropology, 4th ed., 117–35. London: Pluto Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt183p184.11.

Evans-Pritchard, E. E. 1940. The Nuer: A Description of the Modes of Livelihood and Political Institutions of a Nilotic People. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. (1940) 2002. “Nuer Politics: Structure and System.” In The Anthropology of Politics: A Reader in Ethnography, Theory, and Critique, edited by Joan Vincent, 34–38. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Fortes, Meyer. 1953. “The Structure of Unilineal Descent Groups.” American Anthropologist 55 (1): 17–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/664462.

Gough, Kathleen. 1961. “Nayar: Central Kerala.” In Matrilineal Kinship, edited by David Murray Schneider and Kathleen Gough, 298–384. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hua, Cai. 2001. A Society Without Fathers Or Husbands: The Na of China. New York: Zone Books.