Table of Contents

Spheres of exchange in historical perspective

Spheres of exchange in historical perspective

Week 4: Spheres of exchange & The efflorescence of exchange

Ryan Schram

ANTH 1002: Anthropology in the world

Monday, August 22, 2022

Slides available at https://anthro.rschram.org/1002/2022/4.1

Main reading: Sharp (2013)

Other reading: Bohannan (1959); Bohannan (1955); Sahlins (1992)

Bohannan’s prediction

Historically the people of TIv in northern Nigeria classified all of the objects of value in one of three ranked categories.

Items within the same category could be exchanged for each other, but to convert items from a higher category to a lower category was shameful and immoral.

- Women as wives

- Brass rods, tugudu cloth, other prestigious items

- Food, livestock, tools, and other common, everyday items.

Bohannan claimed that money would disrupt the separation of spheres of exchange. However…

- Money was initially placed in the lowest of spheres, or even outside of the three spheres (Bohannan 1955, 68). It continued to mainly be exchanged against low-ranking items (Parry and Bloch 1989, 13–14).

- Other scholars have noted that money does not have this revolutionizing effect on similar systems (Hoskins 1997, 186–88).

Why was Bohannan’s prediction wrong?

Why was Bohannan so confident that the Tiv multicentric economy would become a unicentric economy in which every valuable thing had a price in money?

Bohannan understands people’s values as an anthropologist, but when he considers social and cultural change, he thinks in ethnocentric terms.

- Bohannan, who was born and raised in the US (a unicentric economy in his terms), assumed that his present was the Tiv people’s future.

Is a society in which commodity exchange dominates truly a unicentric economy? Is everything for sale?

An editorial decision

Portland, Oregon, 1997. The Reed College Quest editors meet to discuss an inquiry about a classified ad.

Nobody involved can remember what it said. It was something like this:

“WANTED Healthy female student to help bring joy to an infertile couple. Will pay $3000 plus all medical expenses for a donation of several eggs. Candidates should have a minimum GPA of 3.5 and minimum combined SAT scores of 1600.”

(GPA: grade point average, 3.5 is approximately a WAM of 80. SATs are college entrance exams. Under the old system, 1600 would have been close to an ATAR of 95.)

Human trafficking?

A friend recalls similar ads in student publications at a university in Vancouver, British Columbia. “We had ads at my college in Canada too, even though selling eggs isn’t legal there. I guess they would ship you to the US for the procedure” (personal communication, 2014).

What the ads ask for

- University students (women who have more and better-quality ova).

- Preferred hair and eye color.

- Preferred race.

- Preferred school. Ivy-league (Harvard, Yale, etc.) schools are especially popular, as are Berkeley and Stanford.

Not for sale?

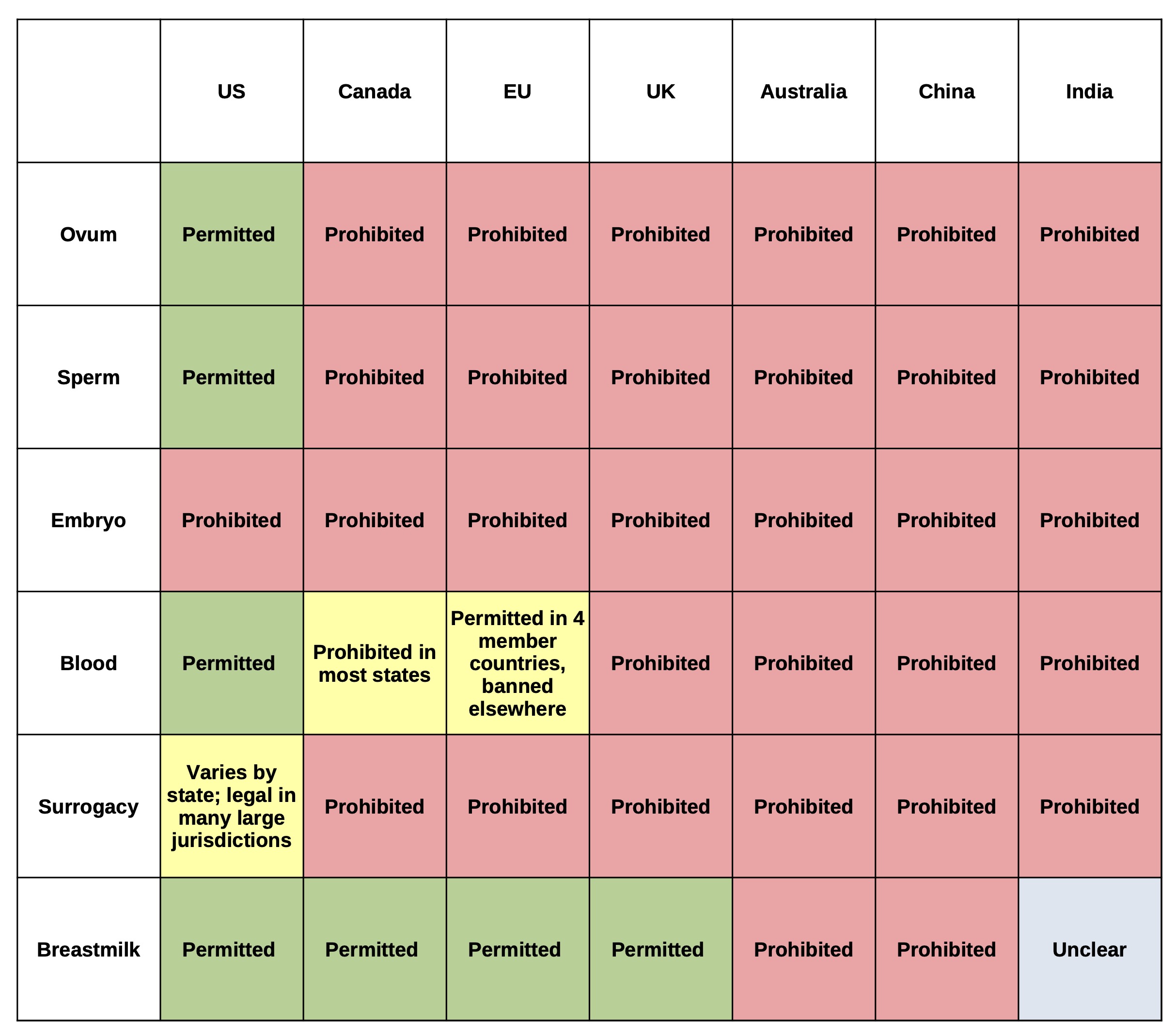

Unlike many countries, the sale of gametes is largely unregulated in the US, and the US has generally looser regulations on IVF and surrogacy. (PDF version.)

Table: A comparison of the legal status of the commercial sale of different kinds of human tissue and surrogacy services in several different countries and jurisdictions. <html>(See Bencharif 2022; Birmingham 1998; Brandt, Wilkinson, and Williams 2021; Burkitt 2011; Cattapan and Baylis n.d.; Caulfield et al. 2014; Davis and correspondent 2022; Jaworski 2020; Klitzman and Sauer 2015; Legislative Services Branch 2020; Nagarajan 2022; “Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act, 2021” 2021; “Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021” 2021; Pollack 2015; Smith, Cohen, and Cassidy n.d.; Yadav n.d.; Zheng 2017.)</html>

Tiv spheres in a colonial context

According to Guyer (2004), the Tiv spheres of exchange are not a tradition, and not frozen in time. They are a historical phenomenon.

- Brass rods work like a kind of currency (noted also by Bohannan), but this a medium of exchange that Tiv keep out of the hands of banks.

- Cash transactions are morally judged, but not because spending money is prohibited or sinful. Money-exchange means a loss of control over Tiv people’s collective wealth as a community. Suspicion of money is a political statement.

Taro gardening in Wamira, PNG and Luo land ownership in Kenya

One of the ways societies respond to market forces is by placing limits on individual choices

- Wamira (Papua New Guinea) taro gardens can’t be tended with metal tools (Kahn [1986] 1993)

- When Luo (Kenya) people sell land, they earn “bitter money” (Shipton 1989)

Inside of every contemporary society, there are two competing principles

A provisional conclusion

- Every society is based on the obligations of reciprocity, even if the weight of these obligations is not visible to the people in that society.

- All societies have at least two spheres of exchanges: things you can exchange (for money) and things you cannot.

- No society exists in isolation, and today every society is part of a larger history of the expansion of global capitalism and its core social institutions: private property, the commodity, and the alienation of value.

- But the story of gifts and commodities is not a from–to story: No society is simply walking from gift exchange, reciprocity, and interdependence to alienation, individualism, and commodity consumption.

- Both the logic of the gift and the logic of the commodity coexist in every society.

- These two systems are based on completely contrary ways of being and thinking, so they often enter into conflict and opposition.

- This is not the only way they interact, as we will see in the next lecture.

References and further reading

“Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act, 2021.” 2021, December. http://indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/17031.

Bencharif, Sarah-Taïssir. 2022. “Blood Money: Europe Wrestles with Moral Dilemma over Paying Donors for Plasma.” POLITICO. April 21, 2022. https://www.politico.eu/article/blood-money-europe-wrestles-with-moral-dilemma-over-paying-donors-for-plasma/.

Birmingham, Karen. 1998. “Chinese Introduce First Blood Law.” Nature Medicine 4 (2): 139–39. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm0298-139c.

Bohannan, Paul. 1955. “Some Principles of Exchange and Investment Among the Tiv.” American Anthropologist, New Series, 57 (1): 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1955.57.1.02a00080.

———. 1959. “The Impact of Money on an African Subsistence Economy.” The Journal of Economic History 19 (4): 491–503. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700085946.

Brandt, Reuven, Stephen Wilkinson, and Nicola Williams. 2021. “The Donation and Sale of Human Eggs and Sperm.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Winter 2021. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/gametes-donation-sale/.

Burkitt, Laurie. 2011. “Chinese Mothers Have Breast Milk, Will Sell. Anyone Buying?” Wall Street Journal, June 14, 2011, sec. China Real Time Report. https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-CJB-13912.

Cattapan, Alana, and Françoise Baylis. n.d. “Paying Surrogates, Sperm and Egg Donors Goes Against Canadian Values.” The Conversation. Accessed August 3, 2022. http://theconversation.com/paying-surrogates-sperm-and-egg-donors-goes-against-canadian-values-94197.

Caulfield, Timothy, Erin Nelson, Brice Goldfeldt, and Scott Klarenbach. 2014. “Incentives and Organ Donation: What’s (Really) Legal in Canada?” Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease 1 (May): 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/2054-3581-1-7.

Davis, Nicola, and Nicola Davis Science correspondent. 2022. “Growing Sales of Breast Milk Online Amid Warnings about Risks.” The Guardian, February 19, 2022, sec. Society. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/feb/19/growing-sales-of-breast-milk-online-amid-warnings-about-risks.

Guyer, Jane I. 2004. Marginal Gains: Monetary Transactions in Atlantic Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hoskins, Janet. 1997. The Play of Time: Kodi Perspectives on Calendars, History, and Exchange. Berkeley: University of California Press. https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft0x0n99tc&chunk.id=d0e7605&toc.depth=1&toc.id=d0e7388&brand=ucpress.

Jaworski, Peter M. 2020. “Not Compensating Canadian Blood Plasma Donors Means Potentially Risky Reliance on Foreign Plasma.” The Conversation (blog). August 14, 2020. http://theconversation.com/not-compensating-canadian-blood-plasma-donors-means-potentially-risky-reliance-on-foreign-plasma-143970.

Kahn, Miriam. (1986) 1993. Always Hungry, Never Greedy: Food and the Expression of Gender in a Melanesian Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Klitzman, Robert, and Mark V. Sauer. 2015. “Creating and Selling Embryos for ‘Donation’: Ethical Challenges.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 212 (2): 167–170.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2014.10.1094.

Legislative Services Branch. 2020. “Consolidated federal laws of Canada, Assisted Human Reproduction Act.” June 9, 2020. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/a-13.4/page-1.html#h-6052.

Nagarajan, Rema. 2022. “Sale of Breast Milk Raises Eyebrows.” Times of India, July 3, 2022. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/sunday-times/sale-of-breast-milk-raises-eyebrows/articleshow/92623732.cms.

Parry, Jonathan, and Maurice Bloch. 1989. “Introduction: Money and the Morality of Exchange.” In Money and the Morality of Exchange, edited by Jonathan Parry and Maurice Bloch, 1–32. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pollack, Andrew. 2015. “Breast Milk Becomes a Commodity, With Mothers Caught Up in Debate.” The New York Times, March 20, 2015, sec. Business. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/21/business/breast-milk-products-commercialization.html.

Sahlins, Marshall. 1992. “The Economics of Develop-Man in the Pacific.” Res 21: 13–25.

Sharp, Timothy L. 2013. “Baias, Bisnis, and Betel Nut: The Place of Traders in the Making of a Melanesian Market.” In Engaging with Capitalism: Cases from Oceania, edited by Kate Barclay and Fiona McCormack, 227–56. Research in Economic Anthropology 33. Bingley, Eng., UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Shipton, Parker. 1989. Bitter Money: Cultural Economy and Some African Meanings of Forbidden Commodities. Washington, D.C.: American Anthropological Association.

Smith, Julie P., Mathilde Cohen, and Tanya M. Cassidy. n.d. “Behind Moves to Regulate Breastmilk Trade Lies the Threat of a Corporate Takeover.” The Conversation. Accessed August 3, 2022. http://theconversation.com/behind-moves-to-regulate-breastmilk-trade-lies-the-threat-of-a-corporate-takeover-152446.

“Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021.” 2021, December. http://indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/17046.

Yadav, Pooja. n.d. “Explained: Why Commercialisation Of Mother’s Milk Is Raising Ethical Questions.” IndiaTimes. Accessed August 3, 2022. https://www.indiatimes.com/explainers/news/why-commercialisation-of-mothers-milk-is-raising-ethical-questions-574550.html.

Zheng, Sarah. 2017. “Chinese Mums Cash in on Latest and Lucrative Craze: Selling Surplus Breast Milk.” South China Morning Post. June 7, 2017. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/2097293/chinese-mums-cash-latest-and-lucrative-craze-selling-surplus.