Mill’s methods of difference and agreement

Societies of the world, whether large or small, are different in many ways and similar in many ways.

Like several other social sciences, anthropology is interested in more than just description and documentation. It wants to know why, and it will often turn to comparison among several cases to understand why some societies are different than others, and why some societies are similar.

John Stuart Mill ([1843] 1882), a philosopher of the 19th century who had an interest in societies and their differences, provides a framework for thinking systematically and drawing conclusions from comparison. Two of the methods of comparison he proposes are the most important.

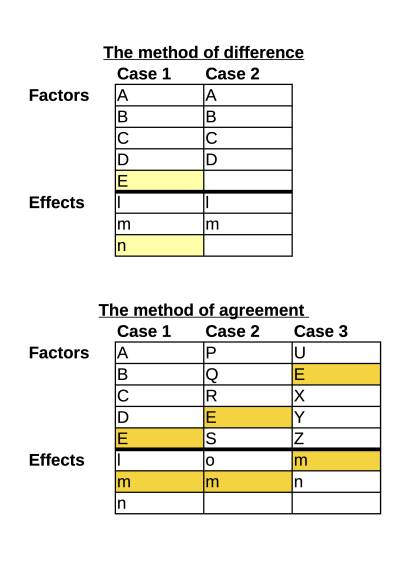

Figure 1: Two of Mill’s methods of comparison (PDF version).

The first is what he calls the “method of difference” (Mill [1843] 1882, 282; see figure 1). Imagine that you have two cases related to something you’re interested in explaining. These two cases are very different in several ways. You could consider all the specific information about them: who, what, where, when. You may also note that the phenomenon you want to explain n appears in one but not in the other. Among all the other factors that you can observe, which is present in one case but absent in the other? In Figure 1, n only occurs in Case 1, in the presence of E. Case 2 lacks E and also lacks n, but is similar in all other respects. Hence, we conclude that E is the reason for n.

Unlike other social sciences, anthropology generally does not have a lot of cases that are very similar. We assume that people are different, and that every society and situation in which people live together is particular to a cultural context. It is more common for anthropologists to use another of Mill’s methods: “the method of agreement” (Mill [1843] 1882, 278-282; see figure 1). Here we look for similarities among a range of cases that are different in every other way. If all of these cases have one factor in common, then we can infer that this is the reason for one phenomenon that they also share.

Marshall Sahlins is very well known for this kind of argument, and with his tongue in cheek he has been known to say that he writes “among-the” texts (Sahlins 2012, 2). He will often draw upon many, many ethnographic case studies—many written in the days of Evans-Pritchard, when anthropologists tended to assume that each society existed in relative isolation—in other words, ethnographies of life “among the Nuer” or some other named society (e.g. Bohannan 1955; Carsten 1995; Evans-Pritchard 1951).

Other social sciences would say that the method of difference is more powerful. With the method of agreement, you can’t ever be sure that you won’t eventually find a case with P, X, Q, T, Z and which also has m. They would argue that social scientists should emulate natural scientists, and conduct comparisons as much as they can like laboratory experiments. In other words, because the method of difference is a controlled comparison, then it is a stronger basis for a causal claim.

Mill offers a partial defense of anthropology’s preference for the method of agreement (Mill [1843] 1882, 283): We live in the real world, not a laboratory. The real world is made up of a lot of stuff that is different in many, many ways, often just for no reason at all because of random chance. Hence, we cannot always be sure that we are comparing a “control group” and a “treatment group” which are the same in absolutely every way except for the one factor we want to investigate as a cause. So we have to rely on the assumption that the cases we compare are mostly different and different in many ways we may not even see. We can at least improve our understanding by looking for a common factor among many cases.

References

Bohannan, Paul. 1955. “Some Principles of Exchange and Investment Among the Tiv.” American Anthropologist, New Series, 57 (1): 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1955.57.1.02a00080.

Carsten, Janet. 1995. “The Substance of Kinship and the Heat of the Hearth: Feeding, Personhood, and Relatedness Among Malays in Pulau Langkawi.” American Ethnologist 22 (2): 223–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/646700.

Evans-Pritchard, E. E. 1951. Kinship and Marriage Among the Nuer. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Mill, John Stuart. (1843) 1882. A system of logic, ratiocinative and inductive. New York: Harper and Brothers, Publishers. http://archive.org/details/systemofratiocin00milluoft.

Sahlins, Marshall. 2012. What Kinship Is—And Is Not. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Similar pages

- Kinship as social action (11.49%)

- Kinship is culture, not nature (10.71%)

- kinship (42.97)

- nuer (13.51)

- pdf (12.46)

- evanspritchard (12.1)

- carsten (7.83)

- Proposal of possible topics (8.18%)

- investigate (9.45)

- cases (5.29)

- stronger (4.32)

- argument (4.21)

- specific (3.64)

- Difference (6.86%)

- differences (18.26)

- random (12.96)

- different (10.62)

- thinking (6.82)

- difference (5.9)