Table of Contents

Kinship as social action

Kinship as social action

Week 4: Family matters

Ryan Schram

ANTH 1002: Anthropology in the world

Wednesday, August 21, 2024

Slides available at https://anthro.rschram.org/1002/2024/4.2

Main reading: Gilliland (2020)

Other reading: Carsten (1995)

Draw your family

Do as the anthropologists do: Make a kinship diagram of your family.

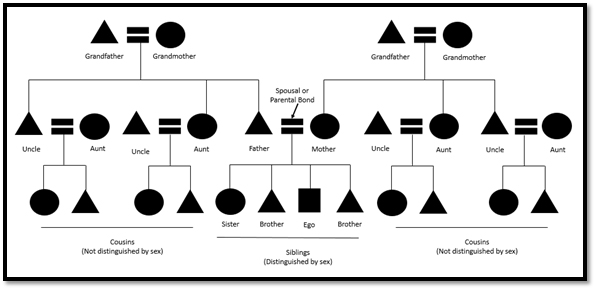

An example kinship diagram using the conventional symbols for people and their genealogical relationships (Gilliland 2020, fig. 2).

Alternatively, make a list of your relatives, and note your relationship to each.

Did you know: No two anthropologists make kinship diagrams the same way. There is no “right” way. Do what you think makes sense.

Kinship as a system of groups, and kinship as a system of exchange

A major theory of kinship argues that the rules by which people trace descent are the mechanism by which people in society are assigned to discrete groups.

Just by tracing each person’s ancestry through their mother or father, a society places each person in a distinct unilineal descent group:

- Matrilineal descent group

- Patrilineal descent group

When people apply the rule of unilineal descent as the criterion for membership in a group, it creates a structure for the whole society.

Not every society has unilineal descent groups

Claude Lévi-Strauss ([1949] 1969) argues that a society’s rules governing marriage are in fact the basis of a society’s kinship categories.

The universality of the incest prohibition

Lévi-Strauss ([1949] 1969) notes that all societies prohibit “incest” (marriage of relatives), but which marriages count as incest is different everywhere. Another classic problem for anthropology.

- It doesn’t matter which relatives are prohibited as spouses. Only some have to be prohibited.

- If some are prohibited, then a spouse must come from the category of people who are not prohibited. Incest prohibitions are important because they prescribe exogamy (marriage out) of a specific category.

- The significance of the prohibition is for the whole community, not for individuals and their choices.

- In the simplest form, there are two categories, each half of the whole community: marriageable people and unmarriageable people. The people in the first half are required to marry someone in the second half, and vice versa.

- Prohibiting incest (or requiring a degree of exogamy) means that society divides itself in half, and the two halves exchange people.

For Levi-Strauss, marriage is a system of alliances, or a system of exchange among groups in which people are the gifts. Marriage rules are in that light a system of reciprocity; kinship is fundamentally the system of total services.

A lingering bias

Kinship is purely social system of categories, and need not have any connection to biology and reproduction. So what’s with all this talk of marriage, parents, children?

Do people have to form heterosexual, opposite-sex marriages in order for people to have kinship classifications?

Many societies also have this kind of bias when they describe their own kinship

- Auhelawa people say that members of a matrilineal descent group have “one blood” because children inherit their blood from their mothers.

- Users of 23andMe say that people who are relatives have “similar DNA,” because you inherit “DNA” from your parents.

Sexual symbolism is not the only way people talk about kinship

In fact, many other societies have forms of kinship that have nothing to do with heterosexual conjugality, even if they use metaphor of “blood.”

- Nuer “ghost marriages” (or “woman marriage”) allow women to be treated as husbands, and as fathers for purposes of patrilineal descent (Evans-Pritchard 1951, 108–9; see also O’Brien 1977; Krige 1974).

- Societies like Kawelka consist of small groups of people who say that they are all related to each other through men (agnatic kinship), yet there are many, many exceptions. But even non-agnatic kin are still said to have the same male blood in them because they work, live, and eat the food of the group’s land (Strathern 1973).

In many societies people speak of kinship as a natural fact in their “blood,” but that doesn’t only mean their birth to parents.

Other societies think of kinship in terms of something else altogether. They don't assume kinship is essential or fixed.

Why did early anthropologists ignore all these exceptions?

The study of kinship in anthropology reveals a lot about the history of the field.

Early anthropologists focused on kinship because

- it challenged the ethnocentric biases of Europeans (including past anthropologists), and

- by studying people’s genealogical connections and the categories that they used to divide them up, they thought they could examine a society objectively and arrive at scientific explanations for many common forms of kinship, like the cross–parallel distinction and the prohibition on incest.

Making kinship diagrams is very much in this spirit.

- By boiling down masses of information to lines and shapes, we can reveal a lot that is obscure, but

- We also can easily assume that the lines we draw are objective, empirical things, and that a symbol used for one group of people means the same for another group of people somewhere else.

- ◯ = △ means a marriage between a woman and man, and a marriage is a marriage is a marriage.

Classical anthropological theories of kinship are just Western cultural assumptions

David Schneider was dissatisfied with anthropology’s excuses for ignoring the exceptions.

He questioned the assumptions that underlie the classical conception of kinship in anthropology.

To reveal the biases in older model of kinship, he wrote an “ethnography” of his own society:

- American Kinship: A Cultural Account ([1968] 1980) is a study of how white, middle-class people in the US categorize their relatives.

- Schneider and his colleagues were mostly products of this culture, and applied its assumptions to other societies they studied.

American Kinship is more than just a critique of anthropology

- First, it argues that US and other similar mass societies have simplified kinship classifications, but they still have them and they still have social salience, just like in rural, small-scale societies.

- Second, people’s actual relationships to their kin in mass societies matter a lot in everyday life, but their dominant cultural ideas about kinship obscure the practical importance of kinship. Schneider’s ideas help us to show this.

American kinship is a symbolic language for society: Relatives, family, and people you love

For Schneider, people use symbols to represent their kinship relationships.

- Symbols are ideas that stand for other ideas.

- Symbolic thinking is not a choice. A culture teaches people to apply symbols to reality, and everything in one’s reality is sorted into either one symbolic box or another.

The American social world is split into two general domains:

- The order of “nature,” or relationships assumed to be natural and unchanging.

- The order of “law,” or relationships based on rules and conventions (Schneider [1968] 1980, 28–29).

American kinship operates with three key symbolic categories.

- Relatives: people who possess the same “substance” or “shared biogenetic material” (Schneider [1968] 1980, 25)

- Family: people who are relatives, and who also fall into the order of law. Family are close relatives, in a symbolic sense (Schneider [1968] 1980, 62–64).

- Everyone else, strangers, and with whom relates purely as a matter of convention but with whom has no common natural substance.

The category of family is represented by a symbol. They are people whom you love, that is, with whom you have a “diffuse, enduring solidarity” (Schneider [1968] 1980, 97, see also 50-52).

If kinship is not a cultural representation of reproduction, then what is it?

In Egypt and other Arab societies, women nurse each other’s children, and receiving a woman’s milk creates “milk kinship” with her and with other children whom she nurses (Clarke 2007).

- Both milk siblings and blood siblings cannot marry.

- Is there a symbol for milk kinship on a kinship diagram? Does there need to be one?

In Pulau Langkawi, kinship develops through acts of feeding. We need an time-lapse image of relationships, not a diagram, to properly represent them (Carsten 1995).

In rural villages of Bahia State, Brazil, children’s choices about where to eat determine who their parents are (De Matos Viegas 2003).

A postscript: Kinship’s weak link is the proliferation of technical terms

Just because we have specialized, precise terms for people’s relationships doesn’t mean that we understand them better.

We’ve just applied a name to them.

References and further reading

Carsten, Janet. 1995. “The Substance of Kinship and the Heat of the Hearth: Feeding, Personhood, and Relatedness Among Malays in Pulau Langkawi.” American Ethnologist 22 (2): 223–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/646700.

Clarke, Morgan. 2007. “The Modernity of Milk Kinship*.” Social Anthropology 15 (3): 287–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0964-0282.2007.00022.x.

De Matos Viegas, Susana. 2003. “Eating With Your Favourite Mother: Time And Sociality In A Brazilian Amerindian Community.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 9 (1): 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.t01-2-00002.

Evans-Pritchard, E. E. 1951. Kinship and Marriage Among the Nuer. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Gilliland, Mary Kay. 2020. “Family and Marriage.” In Perspectives: An Open Invitation to Cultural Anthropology, edited by Thomas McIlwraith, Nina Brown, and Laura T. de González, 182–203. Arlington, Va.: The American Anthropological Association. https://pressbooks.pub/perspectives/chapter/family-and-marriage/.

Krige, Eileen Jensen. 1974. “Woman-Marriage, with Special Reference to the Loυedu. Its Significance for the Definition of Marriage.” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 44 (1): 11–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/1158564.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. (1949) 1969. The Elementary Structures of Kinship. Edited by Rodney Needham. Translated by James Harle Bell and John Richard von Sturmer. Boston: Beacon Press.

O’Brien, Denise. 1977. “Female Husbands in Southern Bantu Societies.” In Sexual stratification: a cross-cultural view, edited by Alice Schlegel, 109–26. New York: Columbia University Press.

Schneider, David M. (1968) 1980. American Kinship: A Cultural Account. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Strathern, Andrew. 1973. “Kinship, Descent and Locality: Some New Guinea Examples.” In The Character of Kinship, edited by J. Goody, 21–33. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

ANTH 1002: Anthropology and the Global--A Guide to the Unit

Lecture outlines and guides: 1.1, 1.2, 2.1, 2.2, 3.1, 3.2, 4.1, 4.2, 5.1, 5.2, 6.1, 6.2, 7.1, 7.2, 8.1, 8.2, 9.1, 9.2, 10.1, 10.2, 11.1, 11.2, 12.1, 12.2, 13.1, 13.2.

Assignments: Module I quiz, Module II essay: Similarities among cases, Module III essay: Completeness and incompleteness in collective identities, Module IV essay: Nature for First Nations.