Table of Contents

Global gifts

Global gifts

Week 5: Transnational families and global gifts

Ryan Schram

ANTH 1002: Anthropology in the world

Monday, August 26, 2024

Slides available at https://anthro.rschram.org/1002/2024/5.1

Main reading: Wright (2020)

Other reading: Leinaweaver (2010)

What do you want to know?

The cover of a 2024 report on food security in rural PNG (Schmidt et al. 2024).

- What would you ask people if you were there right now?

- Who would you want to talk to?

Write your first thoughts down on a sheet of paper now, and talk to each other when you get stuck.

Family and household

As Carsten notes, when the doing of kinship through care is important, then you don’t really need a long genealogical memory of descent.

- In the Pulau Langkawi community Carsten lived, few people had detailed knowledge of their ancestors, who were usually born elsewhere and migrated (Carsten 1995, 320). What matters are the horizontal ties of care in the present (Carsten 1995, 323).

Imagine conducting a population survey or census in this community. Can you ask about parents and children? Does that matter to understanding people’s economic status, health, or residence?

- For the most part, demographers and other survey research already learned about the diversity of family from anthropology and don’t ask questions with ethnocentric assumptions.

- They ask instead about the members of a household, a group of people living together, irrespective of how they are related.

- But even the idea of “living together” rests on some assumptions about daily routines, economic activity, and the overall social and economic structure of society. You wouldn’t ask people in Pulau Langkawi or Maimafu how long their commute to work is, would you?

What is the best first question for a household survey?

How many children do you have? What does your husband do for work, ma’am?😡- Who are the people who live here? 😕

- Who eats here? 👍

The question “Who eats here?” will tend to reveal a mostly-stable group of individuals who depend on each other on a regular basis. (And Carsten would approve, I think, at least in the context of her Pulau Langkawi project.)

Sending so much more than money

But “Who eats here?” also needs to be culturally contextualized. Why do we assume that the people here are a group that should get special attention in a study of people’s lives?

In many countries, people are members of households, but households don’t have one location—they span continents.

- In 2023, there were about 15 countries for whom the total value of remittances received was 20% or more of the whole economy.

- In 2018, the total amount of money received from overseas as remittances (personal gifts of money) was more than 25% of all foreign trade in at least 35 countries.

- In at least eight countries, remittances sent from overseas were worth more than all of the country’s exports. The top “export” in these countries is people.

- In India, where the value of international remittances is not a major part of the country’s total economy, people received over US$125 billion last year.

- This is larger than the value of exports in hundreds of countries, and is larger than the whole economy of at least 100 countries.

Remittances are like an invisible global economy. Even where remittances are not prominent, they are very valuable to many millions of people. They are for many people the main and perhaps only involvment they have in global capitalism. And they are a major part of global capitalism itself.

(For these facts about remittances, see the charts and tables available at the World Bank Open Data web site, especially World Bank 2024a; World Bank 2024b.)

Come rain or come shine

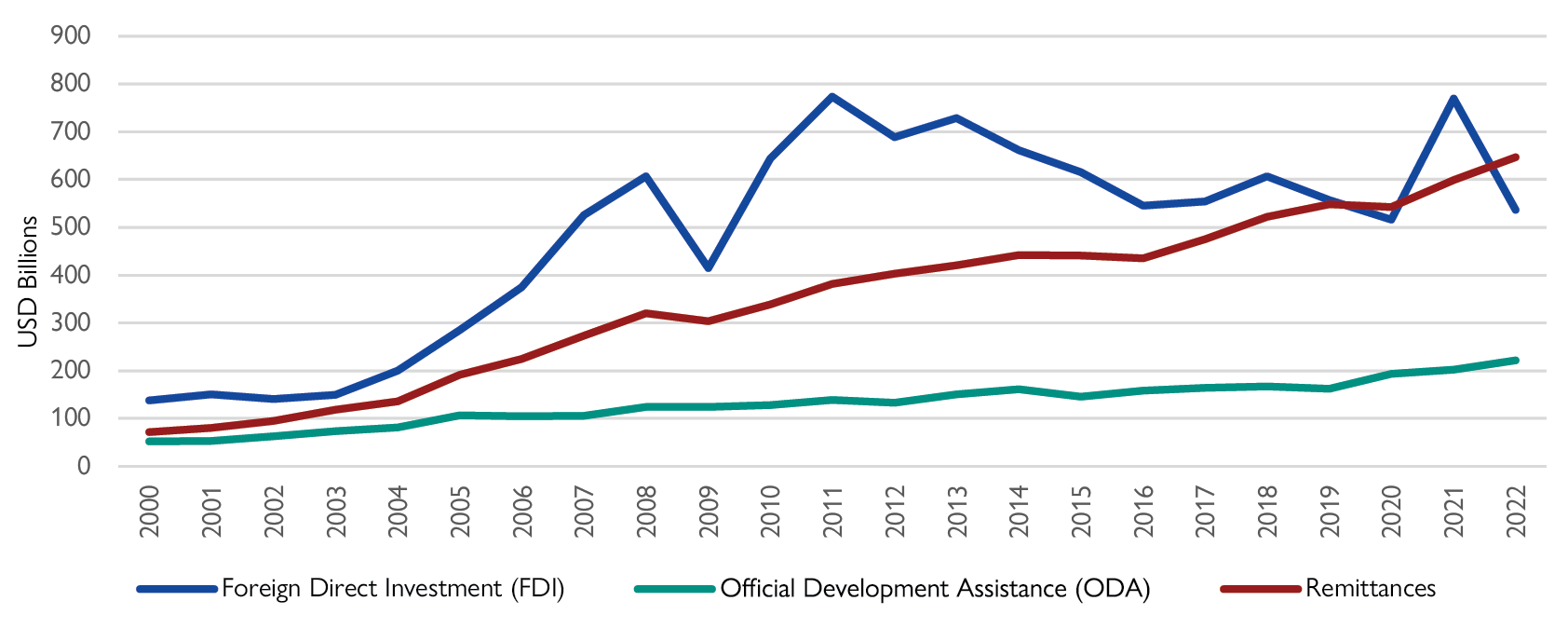

From 2009 to now, the global economy has been on a rollercoaster ride. But in the background, labor migrants keep sending more and more money home.

A chart showing the trends over time of foreign direct investment, overseas aid, and remittances (“International Remittances” 2024).

Stories of migration

What do remittances mean?

- A world that is getting more and more unequal?

- A new way of doing kinship that extends other practices of care?

People learn to read the presence of immigrants in their society through the lens of narratives of migration

In the film An American Tail (Bluth 1986), a family of mice become new citizens in a “nation of immigrants.” Migration is a symbol, something that stands for something else.

- Moving symbolizes change and liberation of oneself as an individual.

- Migrants cut their ties, uproot themselves, move from an “old country” to a “new frontier” to seek their own fortune, and start a new life.

Despite these powerful migration narratives, there are a lot of other ways to be a migrant

- Migration as circulation, return, and reunion

- Migration is temporary, and linked to a future transition.

- Migration uses and maintains links to the home and to one’s existing relatives.

Each is an alternative perspective on the act of migration that one can take. Neither is more real or more correct than the other.

In the migration story of reunification, money creates kinship

Sending money home is often not about material or practical concerns. It is not an act of desparation; it’s a specific way of being a global worker, consumer, and citizen.

- A major purpose for remittances sent by Samoans living overseas is faʻalavelave—gifts of money for community projects (Gershon 2012).

- Temporary male migrants from India work to earn money, to buy gold, to give as presents, to support their female kin when they get married. Remittances (of gold) make someone a good brother (Wright 2020).

If you assume that kinship relations are completely different from economic relations, then temporary migration and remittance networks seem strange.

But this is just one example in which the domain of kinship and economic activity are merged. Global capitalism is for many a global informal economy.

References and further reading

Bluth, Don, dir. 1986. An American Tail. Animation, Adventure, Comedy. Universal Pictures, U-Drive Productions, Sullivan Studios.

Carsten, Janet. 1995. “The Politics of Forgetting: Migration, Kinship and Memory on the Periphery of the Southeast Asian State.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 1 (2): 317–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/3034691.

Gershon, Ilana. 2012. No Family Is an Island: Cultural Expertise Among Samoans in Diaspora. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

“International Remittances.” 2024. International Organization for Migration: World Migration Report. 2024. https://worldmigrationreport.iom.int/what-we-do/world-migration-report-2024-chapter-2/international-remittances.

Leinaweaver, Jessaca B. 2010. “Outsourcing Care: How Peruvian Migrants Meet Transnational Family Obligations.” Latin American Perspectives 37 (5): 67–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X10380222.

Schmidt, Emily, Peixun Fang, Mekamu Jemal, Kristi Mahrt, Rishabh Mukerjee, Gracie Rosenbach, and Shweta Yadav. 2024. “2023 PNG Rural Household Survey Report.” Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institution. https://cgspace.cgiar.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/0e75fa44-3fde-4242-9738-50b435df9b9b/content.

World Bank. 2024a. “Personal Remittances, Paid (Current US$).” World Bank Open Data. 2024. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BM.TRF.PWKR.CD.DT.

———. 2024b. “Personal Remittances, Received (Current US$).” World Bank Open Data. 2024. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.CD.DT.

Wright, Andrea. 2020. “Making Kin from Gold: Dowry, Gender, and Indian Labor Migration to the Gulf.” Cultural Anthropology 35 (3): 435–61. https://doi.org/10.14506/ca35.3.04.

ANTH 1002: Anthropology in the world---A guide to the unit

Lecture outlines and guides: 1.1, 1.2, 2.1, 2.2, 3.1, 3.2, 4.1, 4.2, 5.1, 5.2, 6.1, 6.2, 7.1, 7.2, 8.1, 8.2, 9.1, 9.2, 10.1, 10.2, 11.1, 11.2, 12.1, 12.2, 13.1, 13.2.

Assignments: Module I quiz, Module II essay: Similarities among cases, Module III essay: Completeness and incompleteness in collective identities, Module IV essay: Nature for First Nations.