Table of Contents

Climate change adaptation and environmental justice

Climate change adaptation and environmental justice

Week 11: Who’s expected to adapt to climate change?

Ryan Schram

ANTH 1002: Anthropology in the world

Wednesday, October 16, 2024

Slides available at https://anthro.rschram.org/1002/2024/11.2

Main reading: Jessee (2022)

Sink or swim

Figure 1: Simon Kofe, foreign minister of Tuvalu, delivers a speech to the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (COP26) from the water off of Funafuti, the capital of Tuvalu on November 5, 2021 (Handley 2021).

Of the decision to speak from the water, Kofe said, “The statement juxtaposes the COP26 setting with the real-life situations faced in Tuvalu due to the impacts of climate change…”

Drowned out

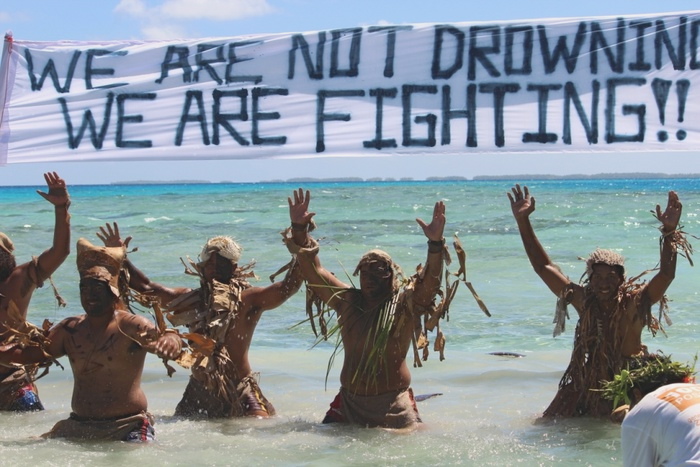

Figure 2: “Tokelau Warrior Dance” (originally published by 350.org). Men wearing Polynesian decorations and shorts stand waist deep in surf with hands raised under a banner reading “We are not drowning! We are fighting!!” during a Warrior Day of Action in 2013 (Carlson 2013).

“We are not drowning; we are fighting” has become a widely used slogan among Pacific climate activists. It was also cited in other remarks at COP26 many years later (Fruean and Kelly 2021).

What are the messages these two different images send?

Our own worst enemy

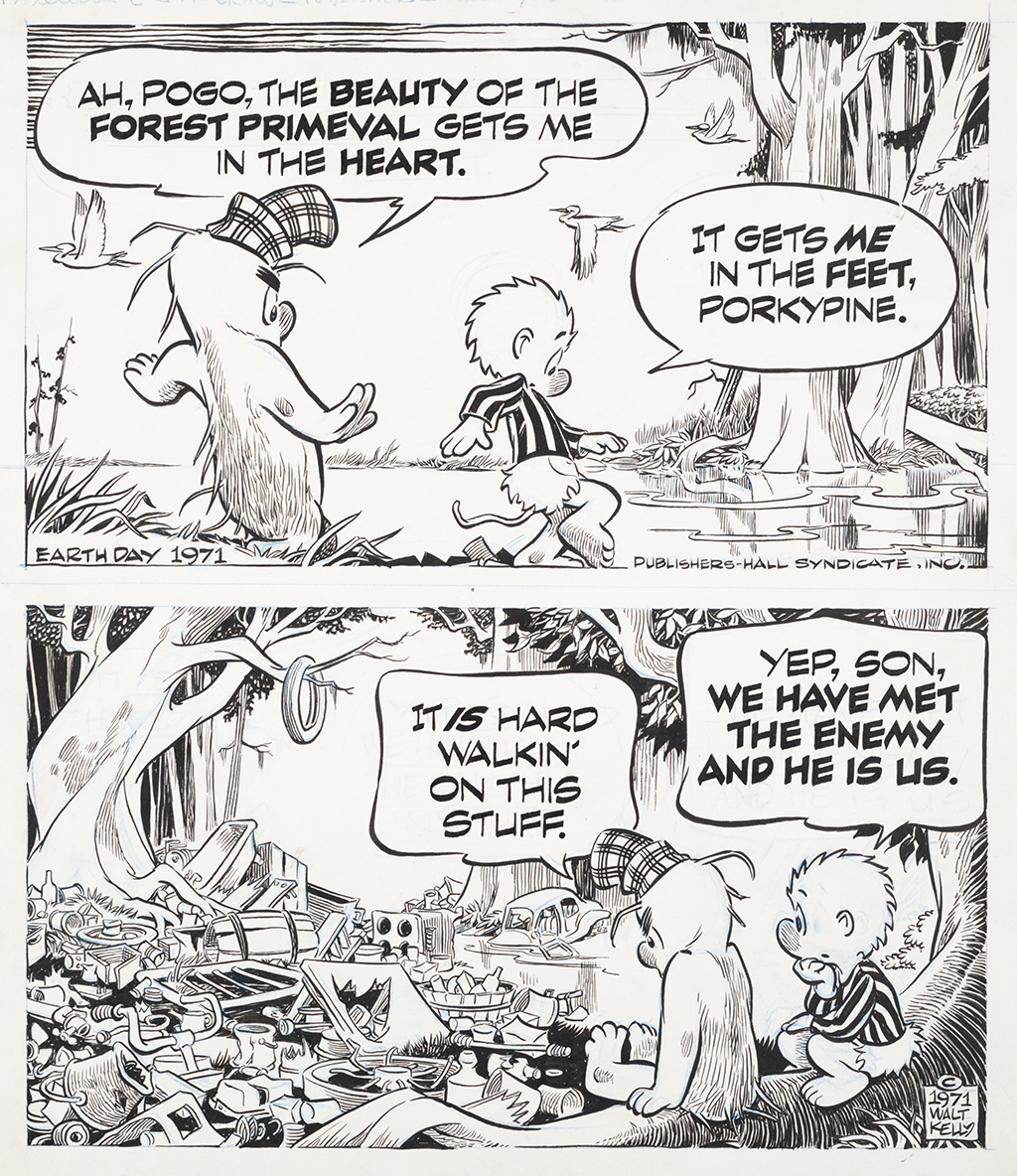

Figure 3: Pogo by Walt Kelly, April 22, 1971 (Kelly 1971). One of several comics produced by Kelly that feature Pogo’s aphorism, “We have met the enemy and he is us,” also most famously appearing in a Pogo Earth Day poster in 1970.

“We have met the enemy and he is us” was first a satire of Cold War paranoia in the United States, but by 1970 became a slogan of the nascent environmental movement (Dunaway 2015, 64–65).

The message? Don’t 💩 where you eat.

Is climate change a symptom of living in a “risk society”?

Ulrich Beck (1992) proposes that we are entering a new phase of modernity, characterized by what he calls a “risk society.”

- The first phase of modernity is defined by the distribution of goods.

- This modernity struggles against poverty. It strives to meet everyone’s material needs.

- The second phase, that of the risk society, must decide how to distribute bads.

- In this modernity, material poverty, though not solved, is solvable. The problem is that the means by which everyone’s needs are met also exposes everyone to new risks. These risks are more important than the “risk” that one cannot meet material needs.

- Some examples of problems faced by the risk society: pollution, nuclear war, nuclear accidents, overpopulation, pandemic disease, the obesity pandemic, antibiotic resistance, the Y2K bug…. And climate change.

Is this the best way to think about sea-level rise in Louisiana or Tuvalu?

Where the risks go

A “sacrifice zone” is not a technical term. It’s a metaphor for how people experience damage to the environment.

- A “sacrifice area” is a term used in the planning and management of grazing lands by livestock; it’s a designated area for the concentration of animal waste or other heavy use (e.g. Johnson 1978).

- An area is sacrificed so that other areas can continue to be used for grazing.

- A report by the US National Research Council noted that federal leases permitting coal mining “[set] in motion a chain of events which ultimately determine whether surface lands… become a ‘national sacrifice area’ (National Research Council (U.S.). Study Committee on the Potential for Rehabilitating Lands Surface Mined for Coal in the Western United States 1974, 183; see also Atwood 1975).

- Anti-nuclear activists also borrowed the term to protest the US government’s testing and development of nuclear weapons (Masco 2006, 222).

- Native American activists used the term to describe US lands degraded by energy mining and exploration (e.g. “Act III: The Declaration of Indian Independence” 1975, 31; Darnovsky 1979, 4).

- Environmental activists, Indigenous rights activists, and scholars have continued to use the term more broadly to highlight how dangerous industrial waste and pollution are concentrated in specific areas, and expose residents to harms to their health (Lerner 2012; Juskus 2023)

The term is dripping with irony. What’s the joke?

How colonialism reshapes space

A frontier is the space beyond the outer edge of a territory. If one zone is governed by law, then the frontier is the limit of that law.

Many societies are based on the myth of the frontier (Weber [1992] 2009; cf. Turner 1921):

- Australia: The myth of terra nullius (no man’s land).

- The United States, Canada: The myth of the “wild West” open for settlement.

- Indonesia: Transmigration programs were a strategy for developing rural areas and creating national unity but, according to critics, were really a “Javanization” effort (Hoshour 1997).

- Tsarist and Soviet Russia viewed Siberia and Central Asia as empty places they could expand into (Bassin 1991).

In reality, no space is empty. What is perceived as an empty frontier is usually a borderlands, a meeting place or “middle ground” (White 1991; see also Reynolds [1981] 2006).

- In the borderlands, different people and communities encounter and interact with each other, and in some way negotiate whether and how they will share space, land, and the natural environment.

The myth of the frontier only makes sense if you sustain a fiction of land as private property, that is, something you can take.

- As Marx says, property is theft; so expansion into a “frontier” is really dispossession of people living in the borderlands (e.g. Li and Semedi 2021).

People are still pretending that borderlands are new frontiers

Mining is digging up nonrenewable resources. Every mine eventually runs dry.

Mining companies need to find virgin land. Since they can’t find it, they make it (Watts 2004).

So-called “sacrifice zones” are places that powerful groups define as empty frontiers.

Low-lying areas are new climate sacrifice zones

Sea levels are rising. This is a delayed side-effect of capitalist expansion, and the dumping of its waste into the atmosphere.

To adapt to sea-level rise, many governments plan to relocate communities: A managed retreat.

This brings us back to the Tuvalu minister’s speech to COP26.

In a managed retreat, governments say they are rescuing powerless people from harm.

But this is a kind of disposssession in another perspective:

- “We’re not drowning [We don’t need rescuing]!”

- “We’re fighting [We want you to deal with us as equals who you’ve harmed]!”

References and further reading

“Act III: The Declaration of Indian Independence.” 1975. Native American Rights Fund Announcements 3 (2 Part 1). https://jstor.org/stable/community.28040948.

Atwood, Genevieve. 1975. “The Strip-Mining of Western Coal.” Scientific American 233 (6): 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican1275-23.

Bassin, Mark. 1991. “Inventing Siberia: Visions of the Russian East in the Early Nineteenth Century.” The American Historical Review 96 (3): 763–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/2162430.

Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk society: towards a new modernity. Theory, culture & society. London: Sage Publications.

Carlson, Keith. 2013. “Photo of the Day: We Are Not Drowning, We Are Fighting!” Mission Blue (blog). March 6, 2013. https://missionblue.org/2013/03/photo-of-the-day-we-are-not-drowning-we-are-fighting/.

Darnovsky, Marcy. 1979. “The Great Uranium Mine Shaft.” Berkeley Barb, April 26, 1979.

Dunaway, Finis. 2015. Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fruean, Brianna, and Jon Kelly. 2021. “My Day at COP26: ‘I Told World Leaders: We’re Not Drowning, We’re Fighting’.” BBC News, November 2, 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-59121480.

Handley, Lucy. 2021. “Pacific Island Minister Films Climate Speech Knee-Deep in the Ocean.” CNBC. November 8, 2021. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/11/08/tuvalu-minister-gives-cop26-speech-knee-deep-in-the-ocean-to-highlight-rising-sea-levels.html.

Hoshour, Cathy A. 1997. “Resettlement and the Politicization of Ethnicity in Indonesia.” Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde 153 (4): 557–76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27865389.

Jessee, Nathan. 2022. “Reshaping Louisiana’s coastal frontier: managed retreat as colonial decontextualization.” Journal of Political Ecology 29 (1): 277–301. https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.2835.

Johnson, Kendall L. 1978. “Managing Livestock Grazing in Relation To Runoff and Erosion.” Rangeman’s Journal 5 (5): 147–49.

Juskus, Ryan. 2023. “Sacrifice Zones: A Genealogy and Analysis of an Environmental Justice Concept.” Environmental Humanities 15 (1): 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-10216129.

Kelly, Walt. 1971. Pogo. “Ah, Pogo, the beauty of the forest primeval gets me in the heart”. Ink, blue pencil, paper. SPEC.CGA.POGO CGA.AC.I5.112. Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum, Oregon State University. https://hdl.handle.net/1811/b03ae202-3afc-495a-b64e-180274101ac9.

Lerner, Steve. 2012. Sacrifice Zones: The Front Lines of Toxic Chemical Exposure in the United States. 1st ed. The MIT Press. Cambridge: The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/8157.001.0001.

Li, Tania Murray, and Pujo Semedi. 2021. Plantation Life: Corporate Occupation in Indonesia’s Oil Palm Zone. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478022237.

Masco, Joseph. 2006. The Nuclear Borderlands: The Manhattan Project in Post–Cold War New Mexico. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691194288.

National Research Council (U.S.). Study Committee on the Potential for Rehabilitating Lands Surface Mined for Coal in the Western United States. 1974. Rehabilitation potential of western coal lands; a report to the Energy Policy Project of the Ford Foundation. Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger Pub. Co. http://archive.org/details/rehabilitationpo0000nati.

Reynolds, Henry. (1981) 2006. The Other Side of the Frontier: Aboriginal Resistance to the European Invasion of Australia. Sydney: UNSW Press.

Turner, Frederick Jackson. 1921. The frontier in American history. New York: Holt & Co. http://archive.org/details/frontierinameric00turn_3.

Watts, Michael. 2004. “Violent Environments: Petroleum Conflict and the Political Ecology of Rule in the Niger Delta, Nigeria.” In Liberation Ecologies: Environment, Development and Social Movements, edited by Richard Peet and Michael Watts, 250–72. London: Routledge. https://api.taylorfrancis.com/content/chapters/edit/download?identifierName=doi&identifierValue=10.4324/9780203235096-15&type=chapterpdf.

Weber, David J. (1992) 2009. The Spanish Frontier in North America: The Brief Edition. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

White, Richard. 1991. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

ANTH 1002: Anthropology in the world---A guide to the unit

Lecture outlines and guides: 1.1, 1.2, 2.1, 2.2, 3.1, 3.2, 4.1, 4.2, 5.1, 5.2, 6.1, 6.2, 7.1, 7.2, 8.1, 8.2, 9.1, 9.2, 10.1, 10.2, 11.1, 11.2, 12.1, 12.2, 13.1, 13.2.

Assignments: Module I quiz, Module II essay: Similarities among cases, Module III essay: Completeness and incompleteness in collective identities, Module IV essay: Nature for First Nations.