Table of Contents

Some history

A history of kinship

Ryan Schram

ANTH 2654: Forms of Families

July 31, 2014

Available at http://anthro.rschram.org/2654/1

Who do you think you are?

Faces of America

Recap

There's lots of reasons to study kinship:

- It raises questions about human nature.

- It seems to explain the social structure of small societies.

- Ideas about family often reveal implicit ideas about gender and morality.

- “Multiculturalism” usually has something to do with the fact that different cultures have differ concepts of family, relatives, and their relationships.

You should choose one reason why you're studying it. What questions do you want answered?

He invented kinship

Many ideas about kinship in anthropology trace back to the work of Lewis Henry Morgan. Morgan gives the first justification for studying kinship as a system of a society.

Every society has its own way of dividing itself into groups and deciding how these groups can relate to each other. The terms we use to label relatives are classifications of people.

Morgan's definition of kinship

For Morgan, kinship is a “system of consanguinity and affinity.”

Consanguinity: related by blood, either through the mother or the father.

Affinity: related by marriage, i.e. a spouse and all of the spouse's consanguineous relatives. Roughly equivalent to English 'in-law'.

Set sail for kinship

W. H. R. Rivers is another “discoverer of kinship” in anthropology.

Rivers collected information about cultures by going out on long expeditions. It was a time before “fieldwork.”

He found that he could gather a clear picture of a society as an organized whole if he just asked a person to name all of their relatives, and to trace their family tree back as far as one could remember. He called it the genealogical method.

Patterns of which relative married which relative were linked to different types of social institution.

Culture shock

Rivers helped create contemporary anthropology based on cultural relativism. For him, marriage forms like polyandry and child marriage were just as strange as cousin marriage among upper-class British families.

A puzzle

Take a piece of paper and write the term. What do you call:

- Your mother's sister's children?

- Your mother's brother's children?

- Your mother's children (besides yourself)?

- Your father's sister's children?

- Your father's brother's children?

- Your father's children (besides yourself)?

You can share answers with neighbors. What languages do people use to talk about these things? How many different terms do we use?

Auhelawa kin terms

Among children of the same parent(s)

- Male speaker, male addressee: tahi or tuwa

- Male speaker, female addressee: nuhu

- Female speaker, male addressee: nuhu

- Female speaker, female addressee: tahi or tuwa

Among grandchildren of the same grandparents:

- The children of sisters call each other by the term …

- The children of brothers call each other by the term …

- The children of a brother and a sister call each other …

X and ||

Because having two types of collateral relatives is so common around the world, anthropologists use English etic (analytical) terms for them:

Cross-cousins are the children of your parents' opposite-sex siblings.

Parallel cousins are the children of your parents' same-sex siblings. (And…?)

And more

The axiom of amity

Meyer Fortes:

Kinship concepts, institutions, and relations classify, identify, and categorize persons and groups. … [T]his is associated with rules of conduct whose efficacy comes, in the last resort, from a general principle of kinship morality that is rooted in the familial domain and is assumed everywhere to be axiomatically binding. This is the rule of prescriptive altruism which I have referred to as the principle of kinship amity and which Hiatt calls the ethic of generosity. (Fortes 2004 [1969]: 231-232)

References

Fortes, Meyer. 2004 [1969]. Kinship and the Social Order: The Legacy of Lewis Henry Morgan. London: Routledge.

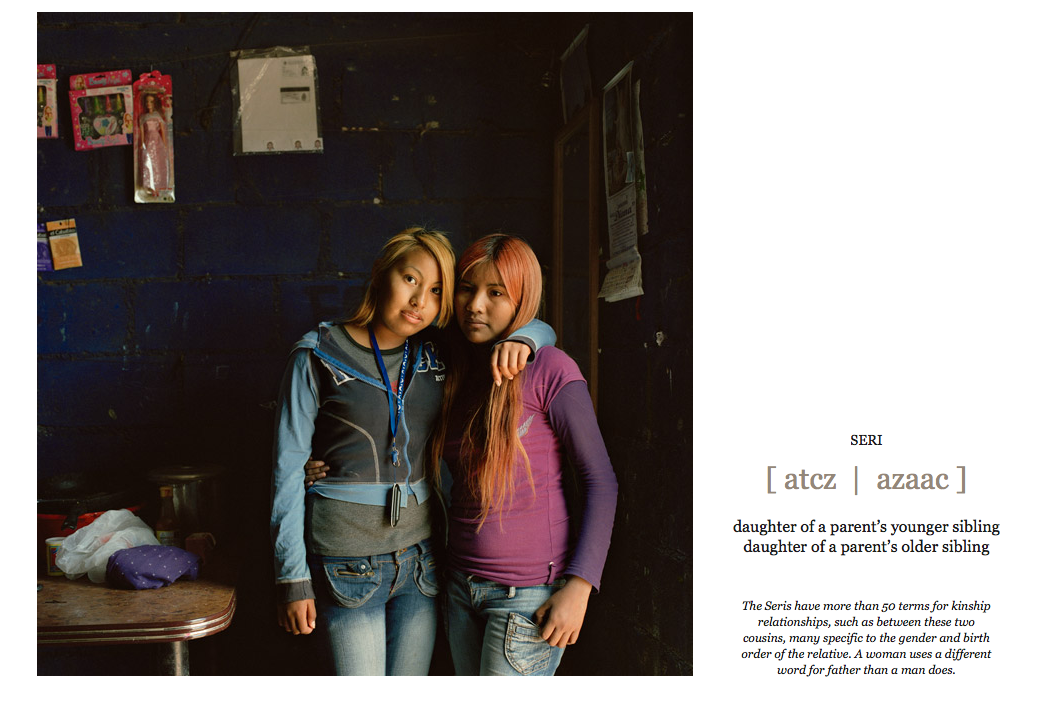

Johnson, Lynn. 2012. Seri Cousins (Photograph). Vanishing Voices Photo Gallery, National Geographic (July). http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2012/07/vanishing-languages/rymer-text